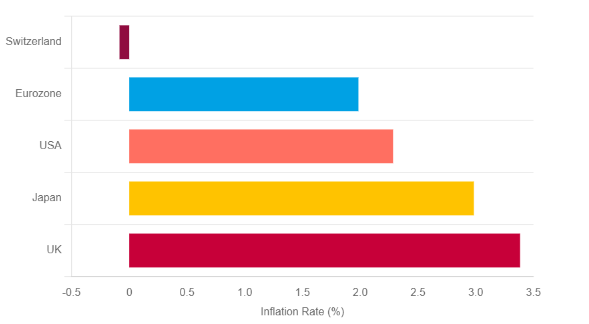

The global economy is being pulled apart. In a great economic tug-of-war defining the second half of 2025, the United States is being yanked in one direction by the inflationary strain of tariffs , while its trading partners are being dragged in the other by a powerful deflationary pull.

This dynamic is overwhelmingly shaped by a single, immense variable: the imposition of broad United States tariffs, which has thrown global trade into a state of unprecedented flux and created asymmetric challenges for the world’s central banks

While some countries like Japan, the Philippines, and Indonesia have secured trade deals to soften the blow, critical negotiations with the European Union and China remain unresolved ahead of looming deadlines, injecting a level of policy uncertainty described as “unusually high”. This has created two opposing macroeconomic problems globally.

The U.S. now faces a stagflationary impulse of slowing growth and tariff-induced inflation. In stark contrast, the rest of the developed world, particularly the Eurozone and Japan, confronts a classic deflationary shock from weakening external demand.

This fundamental asymmetry will dictate the contours of monetary policy and currency performance for the remainder of the year.

The Fed’s Cautious Pivot

The U.S. Federal Reserve finds itself in a state of vigilant pause, having held its key interest rate in a 4.25%-4.50% range through mid-year. This holding pattern reflects a deeply conflicting economic picture that pits the Fed’s dual mandates against each other.

The labor market, while solid, is gracefully decelerating, with hiring plans tempered by economic uncertainty. Simultaneously, the inflationary pressures from new tariffs are undeniable, with businesses across all twelve Fed districts reporting rising costs being passed on to consumers.

This presents the Federal Reserve with a stagflationary challenge: a combination of upward pressure on prices and downward pressure on growth. The Fed’s own median projection points toward two 25 basis point rate cuts by the end of 2025, suggesting a year-end policy rate of 3.75%-4.00%. However, the committee is far from unified, with a significant faction seeing no cuts at all this year.

The baseline forecast is for the Fed to remain on hold through the summer to assess the tariff impact before delivering one or two cuts late in the fourth quarter as the economic slowdown becomes more apparent.

This strategy involves a “look through” dilemma, where the Fed must tolerate a temporary, tariff-driven inflation spike to avoid needlessly damaging a slowing economy, a politically perilous path to navigate.

China’s Precision Easing

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) is expected to continue its policy of “moderately loose” and highly targeted easing to support the world’s second-largest economy. Unlike its Western peers, the PBOC’s approach is a response to deep structural headwinds, including a protracted property sector crisis and weak domestic consumption.

Rather than implementing aggressive, broad-based rate cuts, the PBOC will continue to rely on precision tools like cuts to the Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR) and directed lending facilities. This allows it to channel credit to priority sectors while navigating its “Managed Stability Trilemma”.

The paramount objective is maintaining the “basic stability of the RMB exchange rate” to prevent destabilising capital outflows, a constraint that precludes major cuts to benchmark interest rates. Therefore, the outlook for the second half of the year is for continued targeted liquidity injections with no change to the main policy interest rates.

Japan’s Stalled Normalisation

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) is at a precarious juncture, its ambitions of monetary policy normalisation abruptly stalled. After finally raising its key policy rate to 0.5% in January 2025—its highest in 17 years—the central bank has been forced to a halt, citing the “extremely high uncertainties” from U.S. tariff policy.

The external shock threatens Japan’s export-dependent economy, which is already struggling, having seen GDP contract in the first quarter.

This has trapped the BoJ in a “credibility trap”. Having spent decades trying to prove it could generate inflation, it now needs to prove it can act like a conventional, inflation-fighting central bank. However, raising rates further while the economy is being hit by an external shock risks tipping it into recession and forcing a humiliating policy reversal.

Consequently, the BoJ is expected to keep its policy rate on hold at 0.5% for the remainder of 2025, effectively paralysed until the external trade environment improves.

ECB’s Dovish Pivot

The European Central Bank (ECB) is firmly in an easing cycle, a direct response to modest growth and a clear disinflationary trend. Having lowered its main deposit facility rate to 2.00% in June, it is expected to deliver at least one more 25-basis-point cut by September, bringing the rate to 1.75%.

The Eurozone outlook is heavily clouded by the threat of U.S. tariffs and the significant appreciation of the euro, which has surged to levels near $1.18.

This currency strength has become a critical factor in the ECB’s calculus, acting as a “de facto tightening mechanism”. A stronger euro makes imports cheaper, adding to disinflationary pressure, and hurts exports, dampening growth.

This currency-induced tightening works at cross-purposes with the ECB’s rate cuts, forcing it into a more dovish stance simply to counteract the effect of its own currency’s strength. This dynamic reinforces the case for continued policy divergence with the Federal Reserve.

England’s Divided Committee

The Bank of England’s (BoE) Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is navigating a challenging domestic stagflationary environment. The UK economy is saddled with stubbornly high inflation, which is expected to remain well above the 2% target for the rest of 2025, alongside sluggish GDP growth.

As of its June meeting, the MPC held the Bank Rate at 4.25%, but the decision masked a significant dovish tilt, with a narrow 6-3 vote where three members favoured an immediate cut.

This clear division signals a committee leaning towards further easing. The baseline forecast is for one additional 25-basis-point cut in the second half of the year, bringing the Bank Rate to 4.00%. The outlook is further complicated by the UK’s structural vulnerability.

As a country that consistently runs a current account deficit, it relies on attracting foreign capital, making the pound sterling susceptible to shifts in global risk sentiment, which will act as a persistent headwind in the uncertain environment of late 2025.

Swiss Bank Leads Easing

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) has established itself as the most dovish central bank in the developed world. In a pre-emptive move in June, it lowered its policy rate to 0.0% in response to rapidly falling inflation, which dipped into deflationary territory in May.

The SNB’s policy is a constant battle against its own success; its status as a premier safe-haven destination becomes a curse in times of global stress.

International capital fleeing uncertainty causes the Swiss franc to appreciate strongly, which hurts the export-driven economy and imports deflation. Therefore, the SNB is waging a “war on its own safe-haven status,” using monetary policy to make holding francs less attractive.

The June rate cut has set the stage for a return to negative interest rates, with the strong consensus pointing to another 25-basis-point cut in September to establish a new rate of -0.25%.

For financial markets, this profound divergence signals the fading of the U.S. dollar exceptionalism that has defined recent years, creating a strategic case for a structurally weaker dollar as the Fed prepares to cut rates.

However, this path is fraught with considerable risk. The entire outlook is balanced on a knife’s edge, with the primary risk centred on the unpredictable nature of U.S. policy.

A sharper-than-expected global slowdown could paradoxically trigger a powerful safe-haven rally in the dollar, while a more persistent inflation shock could force the Fed into a hawkish pivot, invalidating the core forecast.

As the strategist Peter Drucker warned, “The greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic.”

Ultimately, navigating this complex and uncertain environment will demand constant vigilance and a flexible approach to managing risk.